When narrative turns into cinema: Frederick Forsyth and the art of writing movies that are read.

By Edinson Martínez

HoyLunes – The notes that have finally conquered these pages are the result of repeated attempts to focus ideas on content constantly interrupted by the astonishment of coincidences.

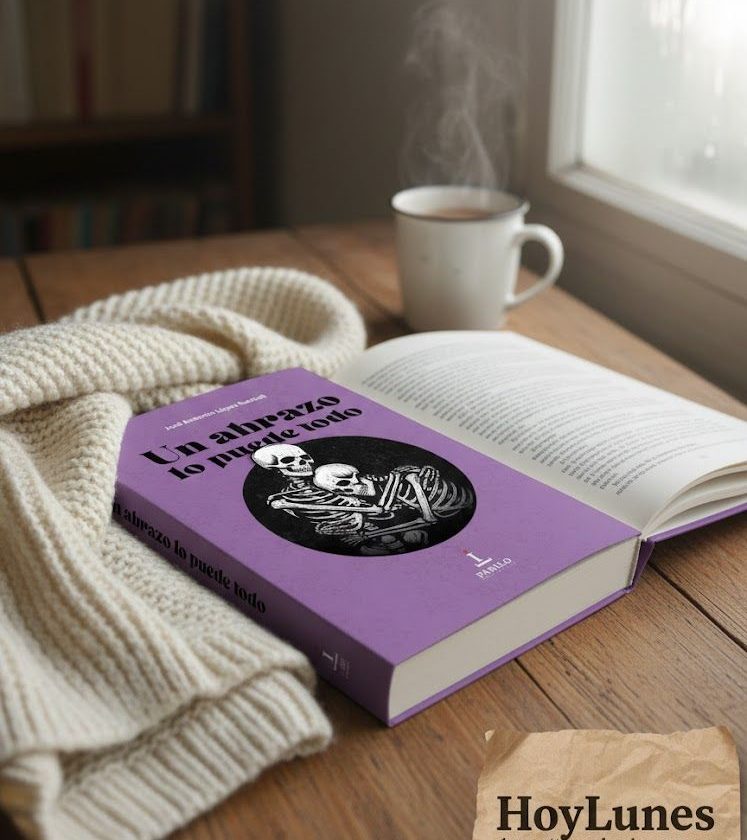

Having just finished reading “The Afghan” and, contrary to my habit, I took a photograph with the book in my hands to immediately post it on my social networks. Incidentally, I thought of sending the same photo to a few friends, recommending at the bottom of the image that they read the novel. The fact is that, while reading it, at several moments I felt as if I were watching a movie. That is why, when I wrote to my friends about it, I simply sent them the photo with the caption: “It reads like a movie. I recommend it”. During the course of its reading, I sometimes wondered whether the events described in the work had actually taken place. And, at the same time, I asked myself whether the novel might already have been made into a film, for it would hardly be surprising if that were the case, given the pen that signed the book.

The Afghan was published in the United Kingdom by Frederick Forsyth in 2006, under the Random House Mondadori imprint, the same publishing house that released it in Spanish at the very beginning of the same year’s winter.

The celebrated British author has several novels adapted into films – “The Day of the Jackal” (1971), “The Dogs of War” (1974), “The Odessa File” (1972). His style astonishes by the admirable interweaving of a narrative written like that of a novelist, while at the same time unfolding the story with the rigor of a meticulous journalist. In the end, the reader could perfectly conclude that what he or she has read—or seen on the screen—is a true story and not a work of fiction.

In his books there is no room for the poetic prose we observe in other novelists of the same genre, or in those bordering on the type of narrative where suspense, anxiety, intrigue, mystery, and uncertainty are the predominant emotions driving the plot. Frederick Forsyth stands out for his work that blends reality with fiction, probing real life and historical events, then masterfully developing them into a fiction that seems to replace reality. There is no space for narrative subjectivity in his works; this is what I perceive when I read them, and that is why I believe it to be his particular hallmark in approaching creation. Perhaps it is this—I happen to think without much analysis—that paves the way for the screenplays based on his texts to achieve the success they have attained as soon as they were projected in movie theaters. I could say that this is his singular alchemy: it may be liked or not, even displeasing to those who seek in a writer’s text a certain intimate flight, a kind of enchanted pleasure with words that reproduce reality.

Between 1976 and 1977, I had the chance to watch the film “The Day of the Jackal“. I was very young then and limited myself to seeing it as a good movie. This film production had been released outside Venezuela in 1973, but around the date I mentioned earlier, it reached the cinema in my city; an unusual screening in a theater accustomed to more mass-consumption commercial films—such as “Rocky” and “The Omen“, coincidentally from the same period.

The screenplay of “The Day of the Jackal” is by Kenneth Ross, based on the novel of the same name by Frederick Forsyth, which had been published in 1971. The publication, once in the hands of readers, very shortly thereafter became a bestseller, with some sources estimating sales at around 75 million copies up to the present. On the big screen, it was likewise a smash box-office hit for several years. However, at the time, it did not occur to me to scrutinize the facts presented in the film. It was not until much later, when I read “The Centurions” (1960) by Jean Lartéguy, a French writer and journalist who, in my opinion, most closely resembles Frederick Forsyth’s style. When I decided to investigate the underlying issue in “The Day of the Jackal“, curiosity led me at that time to search for the novel and read it, and subsequently to inquire further and discover that the events narrated in reality had a historical basis that clearly inspired the work. As likewise happens with “The Centurions“.

Thus, in fact, the assassination attempt to end the life of French President Charles de Gaulle—the core of the film’s plot, and by derivation of Frederick Forsyth’s book—had indeed taken place on August 22, 1962. Of course, the events did not unfold exactly as they are recounted in the story, because in that case, it would cease to be a novel, a work of fiction, as it truly is, and instead become a chronicle or a journalistic document. But certainly, the attack did indeed occur, and moreover, it was an operation that involved snipers who, with millimetric precision, sought to ensure that the head of state would not escape alive, as is vividly portrayed in the film. In the novel, likewise, the entire process of planning and execution of the attack is recounted through the use of historical fiction.

Incidentally, and speaking of the Jackal, I cannot pass up the opportunity to point out what is told about the Venezuelan terrorist Carlos Ilich Ramírez, who gained international notoriety between the 1970s and 1980s as the most wanted man for his attacks and kidnappings in the name of the Palestinian cause. Precisely at the time when the aforementioned film was released.

The fact is that, during his pursuit across several countries, with his identity not yet clearly established, in London a raid was carried out on a residence where he was presumed to be. When the authorities arrived, they did not find him, and instead, among all the evidence collected, they came across a copy of Frederick Forsyth’s book “The Day of the Jackal“. From that moment on, then, for the world press and for European security agencies, the man who would later be identified came to be known as “the Jackal“, a nickname by which he is still referred to.

Well then, returning to the case of “The Afghan“, I must point out that, impressed by the abundance of detail found in its reading, the way in which the work is structured, and the diversity of contrasts and geographical contexts present in it, at certain moments it seemed to me as though I were sitting in a movie theater watching its projection, while at the same time wondering whether this novel might not have already been adapted into a film. I was also struck by the thought of the real foundation of the written story, something similar to the case of “The Day of the Jackal“. The truth is I cannot confirm that a film has been made based on the book; it is very likely, and once I determine whether one exists, I will watch it, and I will do so with the natural expectation of appreciating its fidelity to Forsyth’s written text.

In “The Afghan“, the narrative sequence, the handling of time, the author’s voice, the dialogues, and the entire contextual setting in which the plot develops are, in fact, almost a film. This is an undeniable merit of the British author when he writes his novels, just as the same could be said of the novels of Morris West, the Australian author who likewise has a notable number of works adapted into films.

The backdrop of the work under discussion in these lines is the terrorist attack of September 11, 2001; without that historical event, “The Afghan” could not have been conceived. However, the plot revolves around the struggle against the global threat of Islamic terrorism in the period following the attacks. It is, therefore, a publication that intervenes in an exceptional manner on a subject of burning relevance. Thus, the novel begins with what one might call an unassuming incident that exposes a large-scale terrorist operation on the verge of being carried out. Hence, its narrative unfolds under the dominion of suspense and intrigue. In it, the author does not seek to present us with the prototype of a protagonist in the style of Ian Fleming’s works, nor with the moral dilemmas of characters involved in conspiracies as in the novels of Morris West, another of the greats of the suspense and intrigue genre. Nor a fiction close to that of John Katzenbach, whose texts, certainly full of suspense, do not reach the proportions of documentation, support, and, if you will, political perspective that we find in the literary creation of Forsyth and Jean Lartéguy, who—if compelled to compare them—I would conclude that their works admirably fuse, as I said before, fiction with a journalistic approach that stands out for its investigative rigor in building, with coherent logic, the verisimilitude of the plot. Both are inspired by history, by real conflicts, especially those that, due to their magnitude, shock world communities. It is the journalistic vein, in that sense, the vital nerve that drives them, and they do so without conceding a millimeter in favor of any form of poetic, intimate prose, or narrative identity marked by personal reflection, unlike, for example, Michael Ondaatje, who also explores historical events of the same order but, in this case and in contrast to the aforementioned, incorporates his reflective and emotive voice, subjectively amalgamated with the objectivity he observes.

In “The Afghan“, among other aspects, I was particularly struck by the mention, in some part of the work, of the murder of two Venezuelan sailors in Port of Spain, Trinidad, crew members of a vessel named “Doña María” under the command of a captain, also Venezuelan, named Pablo Montalbán. This event is inscribed within the context of the terrorist plan being plotted by extremists from the other side of the world. When one reads the novel and delves into its details, there is no other option but to regard the writer as someone endowed with an ingenious mind, extremely meticulous, one might even say, to the point of leaving no loose ends in the details of the story.

In a sordid bar beside the dock in Port of Spain, Trinidad, two merchant seamen were assaulted and murdered by a local gang. The stab wounds had been inflicted by expert hands.

When the police arrived, the witnesses were suddenly afflicted with amnesia and could only recall that five assailants had provoked the fight and that they were islanders. […]

[…] They had not tried to steal the wallets of the dead men, so the Port of Spain police were able to identify them immediately: they were Venezuelan citizens and members of the crew of a ship from the same country, still in port.

The details of sending the bodies back to Caracas fell to the Venezuelan embassy and consulate, while Captain Montalbán contacted his local agent to replace the sailors. The man made inquiries and was lucky. He found two young and educated Indians from Kerala eager to sign on, who were paying for a trip around the world with their work and who, though they lacked citizenship papers, carried perfectly valid seamen’s books.

They signed on, joined the other four sailors who made up the crew, and the “Doña María” sailed only one day behind schedule.

Captain Montalbán was vaguely aware that the majority of India’s population was Hindu, but he had not the faintest idea that there were also one hundred and fifty million Muslims”.

The Afghan (2006). Frederick Forsyth

Frederick Forsyth passed away at the age of 86 on June 9, very probably at the very moment I was finishing reading “The Afghan“, and, as if in a precise and mysterious conjunction of quantum hues, I was taking the photograph to send to my acquaintances recommending the book to them. And so, I now reiterate what I said then: Read the novel. It reads like a movie.

#hoylunes, #edinson_martínez,